I recently returned to Little Cayman on a trip with my home-base dive shop, Atlantis Aquatics. Little Cayman is one of my favorite dive destinations and truly is a showcase of the Caribbean’s greatest hits: sea turtles, groupers, stingrays, nurse sharks, and reef sharks are common sightings, as are smaller critters like spotted drums, sea slugs, “disco” fish, and cleaner shrimp.

Most people who visit the Cayman Islands stay in Grand Cayman, the largest and most commercialized of the three islands. Just eighty miles east of Grand are the sleepier sister islands of Little Cayman, and 15 miles further, Cayman Brac. They are remote and undeveloped: no corporate hotel chains, Starbucks, or movie theaters here. These destinations are for people who want to scuba dive, fish, or just disconnect.

Flying to Little Cayman reminds me of travel in the Alaskan bush or the Costa Rican rainforest - small props landing on remote airstrips

Visitors arrive in Little Cayman on a deHavilland Twin Otter— a dual-engine, 18-seat, propeller plane — that departs Grand Cayman and lands thirty minutes later on a tiny airstrip nestled between mangroves and natural coastline. One narrow ring road traces the circumference of the island — you could drive it potentially without seeing any other vehicle traffic.

For this trip I opted to keep the photography kit relatively simple with a one lens wide-angle setup only: my Canon EF 16-35mm F/4L IS lens on a Canon R5 body. I took it underwater in a Nauticam housing with two Sea & Sea strobes. (All of my gear, incidentally, is purchased at Backscatter — and they have presence teaching underwater photography courses at the dive resort where I stayed on Little Cayman.) Although there is plenty of macro life to see in Little Cayman, I find that diving with a group of divers following a dive guide means we don’t spend much time in any given spot, which makes macro photography difficult. Going with a group of other photographers (or diving with only your buddy) is a much better arrangement for macro photography. (Want to learn more about wide-angle vs. macro photography? Check out this video)

One of my goals on this trip was to seek strong subject separation. I have many photos of turtles and barracuda blending into the reef, so on this trip I was hoping to make them “pop” more distinctly in my images. Too often turtles photographed against a reef are overtaken by the busy background, almost camouflaged into the complex array of corals.

A hawksbill turtle flies over the reef. I like this image because there is subject separation so the turtle really stands out. It also clearly shows action and movement.

A great barracuda displays its menacing teeth. Once again, there is good subject separation so it does not blend into the reef. This was shot on the edge of one the of many coral fingers

To achieve subject separation on the reef, the photographer must be lower than the subject and must approach at an upward angle — not easy to do without trampling on the fragile corals, which is of course absolutely forbidden. The trick to this type of shot is to look for subjects near the edge of a slope, coral head, or wall where you can easily dive lower than your subject without touching the reef.

Another goal was to visit a well-known shipwreck in Cayman Brac. On my last visit to Little Cayman this wasn’t an option, so I was excited when the captain proposed a trip (weather permitting) out to the Brac to dive this wreck. Transit time was about 50 minutes in moderately choppy seas, but the bouncy ride was well worth it. The M/V Keith Tibbets, formerly a Soviet destroyer built for Cuba, rests in clear water on beautiful reflective sand. The shipwreck is extremely photogenic, with its forward turrets clearly visible. It is about 90 feet down to the sand, but divers who don’t want to go deep can explore the shallower starboard side at about 60 feet.

The M/V Keith Tibbets, formerly a Soviet destroyer built for Cuba, was a highlight of this dive trip

One topic of debate in diving is whether it is permissible to kneel in the sand. Some dive operators allow it as long as it is done with care; others do not permit it and ask divers to remain buoyant above the bottom. On this trip we were asked not to kneel on the bottom so stingray shots were a bit more challenging, but not prohibitively so.

This was my favorite stingray encounter. It’s fairly common to see rays gliding across the sand, or buried on the bottom, I caught this ray in the process of swirling up the sand and digging itself in.

We had several stingray encounters, and it is remarkable that each ray had its own personality. One was feisty and irritated, more so by the bar jack that was tracing its every movement than any encounters with us. Another was skittish and seemed to take off whenever we got too close. And then there were two others who were very tolerant of our presence, posing in the sand unencumbered even as a group of three of us approached with our cameras. It truly is a pleasure when a subject is cooperative, and it’s no surprise that the best images are achieved when the animal is calm and unbothered by our interactions.

“Schoolmasters’ Tower” is my favorite image from this trip. Here schoolmaster snapper (Lutjanus apodus) rest in the lee of a coral head. If you look closely you can spot a Bermuda Chub and a squirrelfish tucked in among the snapper.

This is really a snapshot split, meant to document the experience of getting back on the boat. Divers are privileged to see a completely different world underneath the surface

With the exception of south Florida, I rarely revisit dive locations within 5 years — there’s always somewhere new or different to explore before recycling old favorites. Little Cayman is an exception, and will continue to be owing to its reliability as an outstanding Caribbean dive destination. See you again soon!

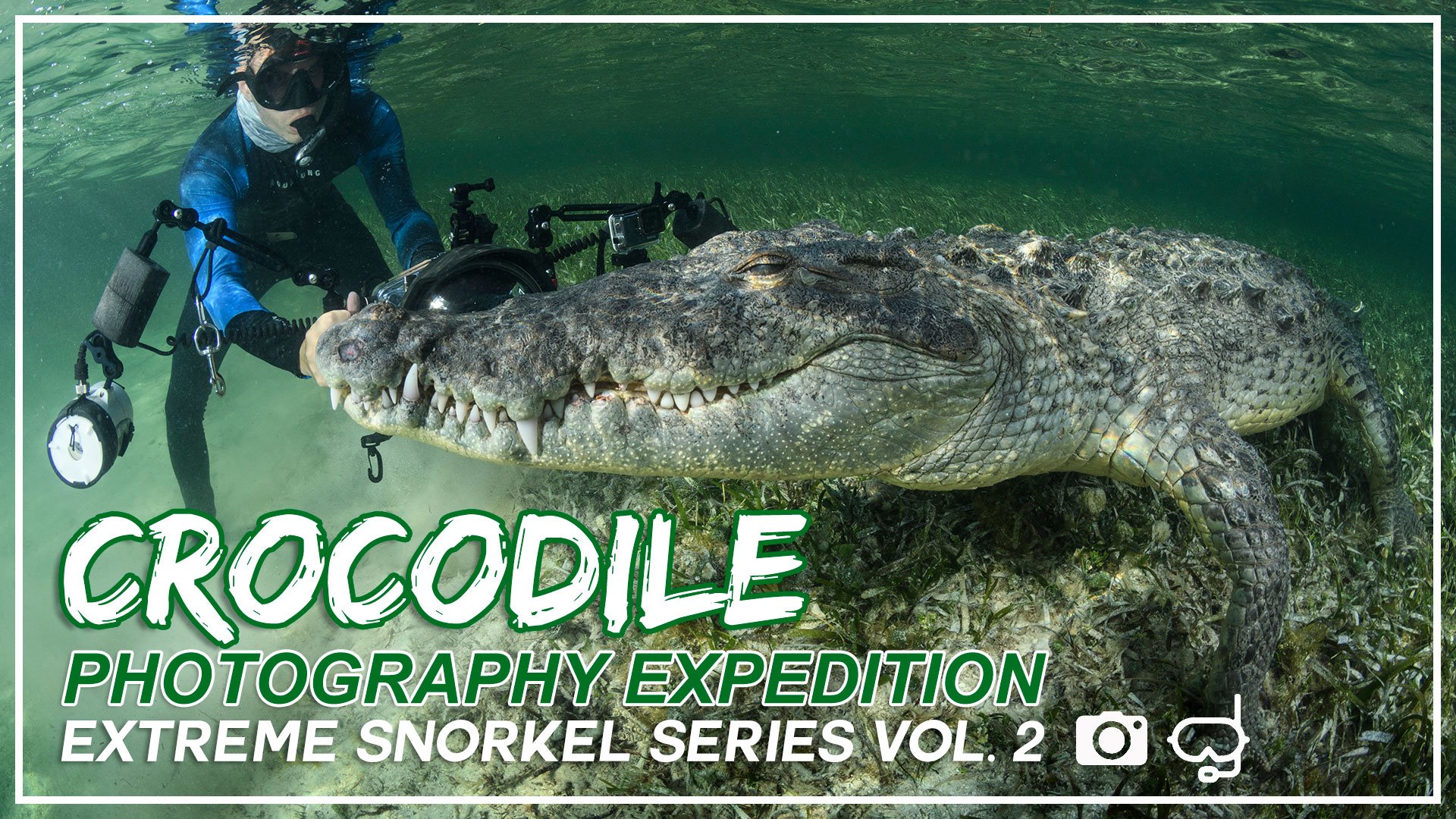

If you are interested in learning about underwater photography, or experiencing some close-up behind-the-scenes encounters with sharks, dolphins, crocodiles, check out my YouTube channel.