FIVE TIPS TO ACHIEVE A GOOD IMAGE

Every landscape photographer has been there: you travel across the globe to a spectacular location, hike for miles, maybe even set up a campsite, and wait for hours to capture your subject in the best light, and … the sunset (or sunrise) is a total bust. I’ve previously shared some tips for photographing during inopportune times and in harsh light, so today we’ll switch focus to when you’re shooting in the best possible times and the sky just doesn’t cooperate. Each of the images we’ll review today resulted from a failed attempt at capturing a colorful sunset (or sunrise).

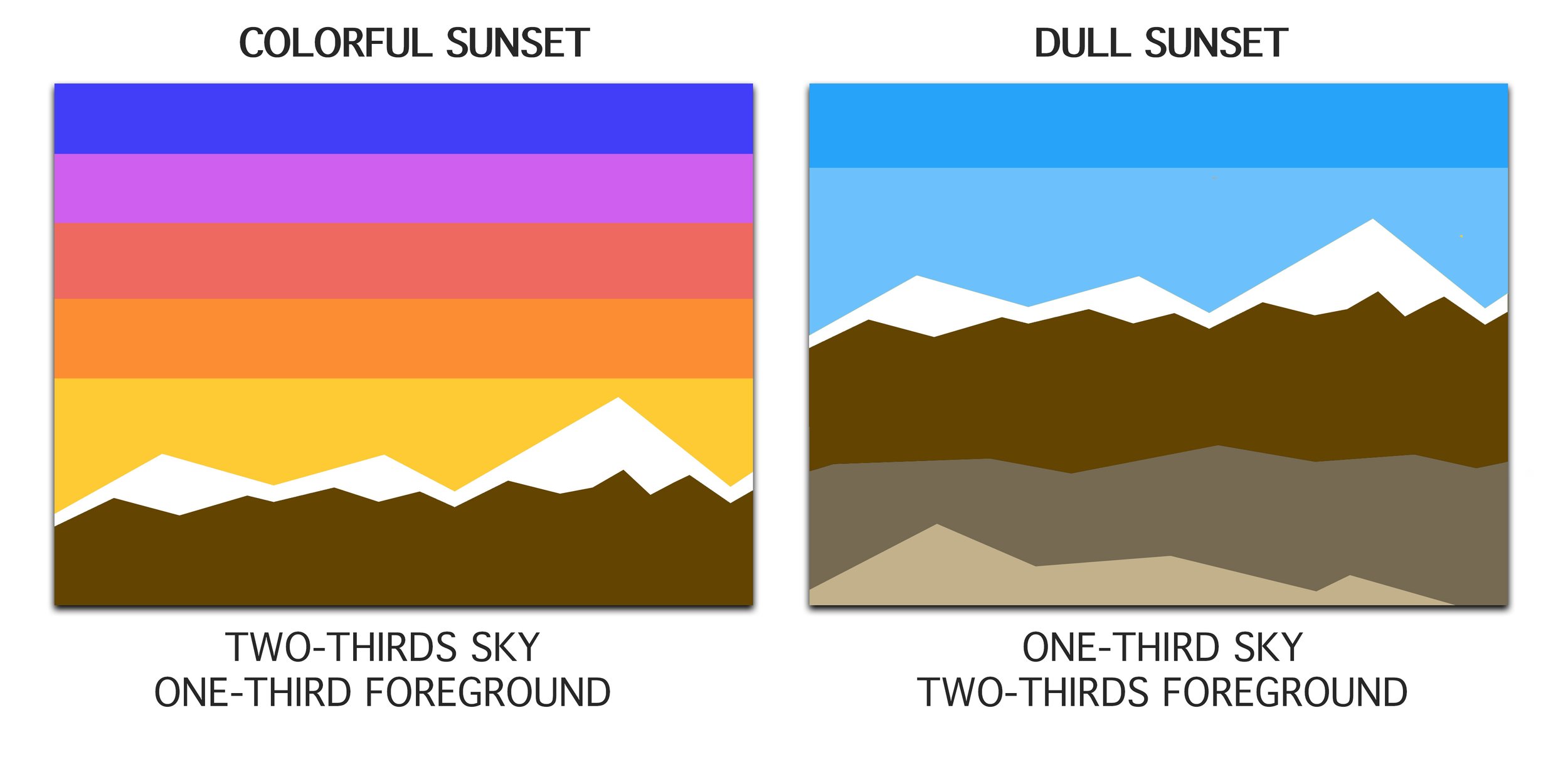

MINIMIZE THE SKY

It may seem obvious, but I’ve seen many photographers in denial force a sunset shot in cloudless boring skies. They’ll compose to include way too much of nothing – better to accept that the sky is not the star of the show, and recompose for a more interesting image. Let’s look at an example below. Admittedly, I could have fared much worse with this sky, but what you see in the image is quite literally the only patch of sky that displayed any color that evening. I initially envisioned a leading line toward the mountain as a foreground element, with about 60% of the image composed for the sky. This image turns that on its head and gives the illusion of a great sunset when in fact it was very limited and unimpressive.

This image gives the illusion of a great sunset – in reality, it was limited to a very small area of the sky

CUT OUT THE SKY ENTIRELY

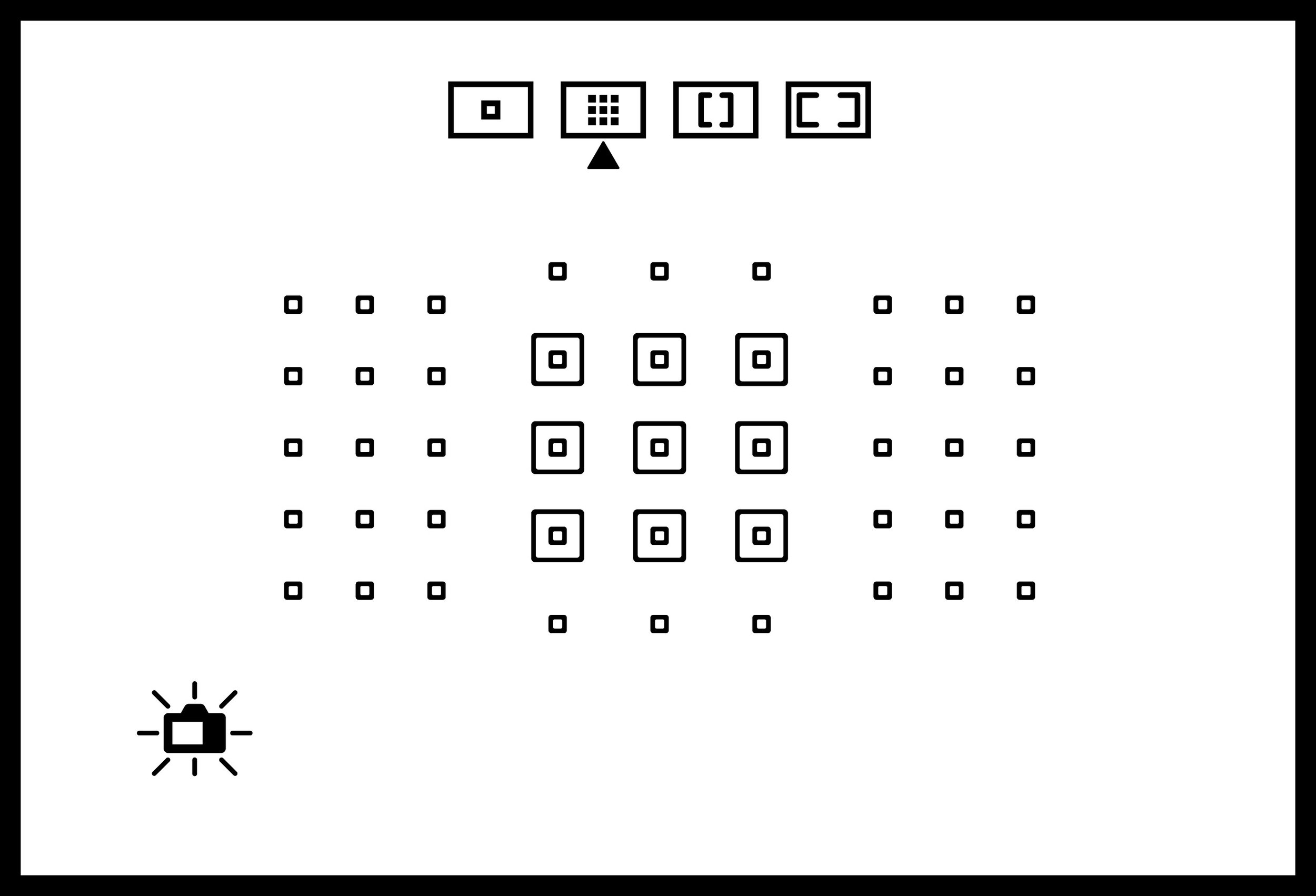

Similar to the previous tip, there are scenes that don’t call for any sky whatsoever. Novice photographers are taught to adhere to the rule of thirds, which in the case of a dull sky implies that only the top one-third of the image should feature the sky, but this formula should be discarded at times for a more creative approach.

Above: The rule of thirds is one of the first compositional principles taught to new photographers. It is a useful concept, but should not be used prescriptively.

In the following two examples, the sky was painfully clear and without any color. The first image was taken at sunset, though you wouldn’t know it since there is nothing in the light quality to suggest it. Eliminating the sky adds some mystery to how steep the waterfall really is (the top is just out of frame, but you can imagine it being much taller). Normally I do not like to include people in my shots, but the woman in red provided such a terrific contrast and sense of scale that I actually hoped she would stay still in that spot for a few minutes (and by pure luck, she did).

There is no requirement to include the sky in your shot, even at sunset or sunrise

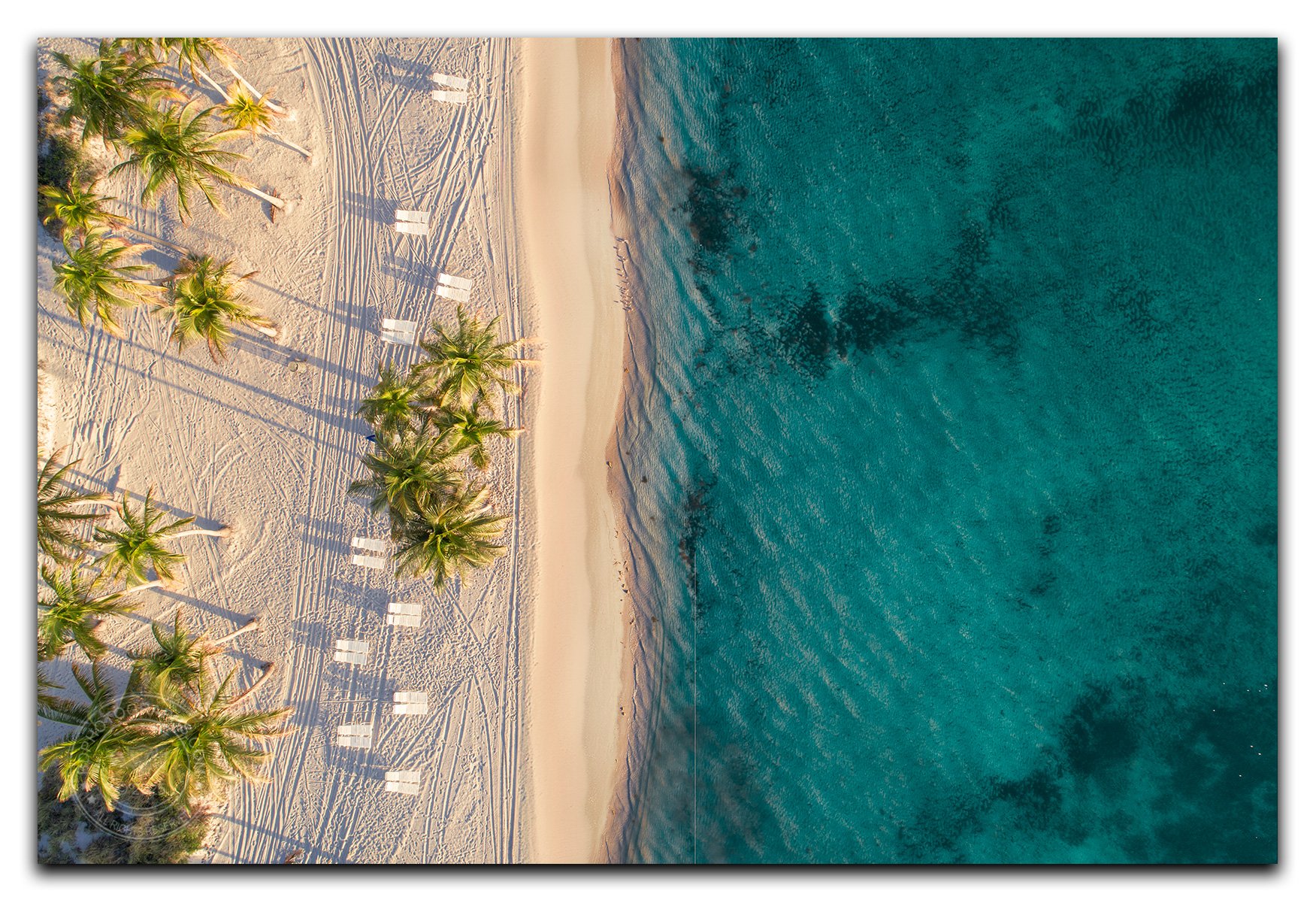

I love top-down drone shots, but rarely think of them at sunset since there is so much emphasis on capturing a colorful sky. This is actually a failed sunrise shot – completely clear skies did not deliver anything worthwhile. Instead, I composed straight down and focused on the long shadows and soft light as the sun peeked over the horizon.

Sunrise did not deliver nice color, but the delicate light and long shadows provided an opportunity for a drone shot

WORK IN THE GOLDEN HOUR

As I’ve developed my photography portfolio over the years, I find golden hour to be my favorite time to shoot. Golden hour is the time when the sun is very low in the sky, usually the final 30 minutes before sunset (or first thirty minutes after sunrise). I visited this location in Death Valley with three shots in mind: a golden hour shot, a sunset shot, and a nighttime milky way shot. I knew that in the dry desert basin clear skies are common, so capturing color in the sky would require some type of weather system. In the end I achieved two out of three shots (the sunset was a bust), and walked away very happy with the result.

Golden hour provides an opportunity to capture long shadows and beautiful light

WORK IN THE BLUE HOUR

Just as golden hour delivers a unique quality of light, blue hour drapes the landscape in a soft, cool, cinematic tone. It is by far my favorite time to shoot cityscapes, and can be a spectacular condition in which to capture landscapes as well. Blue hour occurs after sunset and before full darkness of night. Likewise, the pre-dawn blue hour transitions from the night and ahead of sunrise.

Most photographers visit this location for a sunset capture, but those who stick around into the blue hour will be rewarded with a magical and more original shot

Keep in mind, in lower light conditions it is advisable to shoot with a tripod as you’ll need to take longer exposures. For most of these types of images I shoot with my primary full frame camera and a wide angle lens, or a medium-wide lens.

Blue hour is my favorite time of day to photograph cityscapes

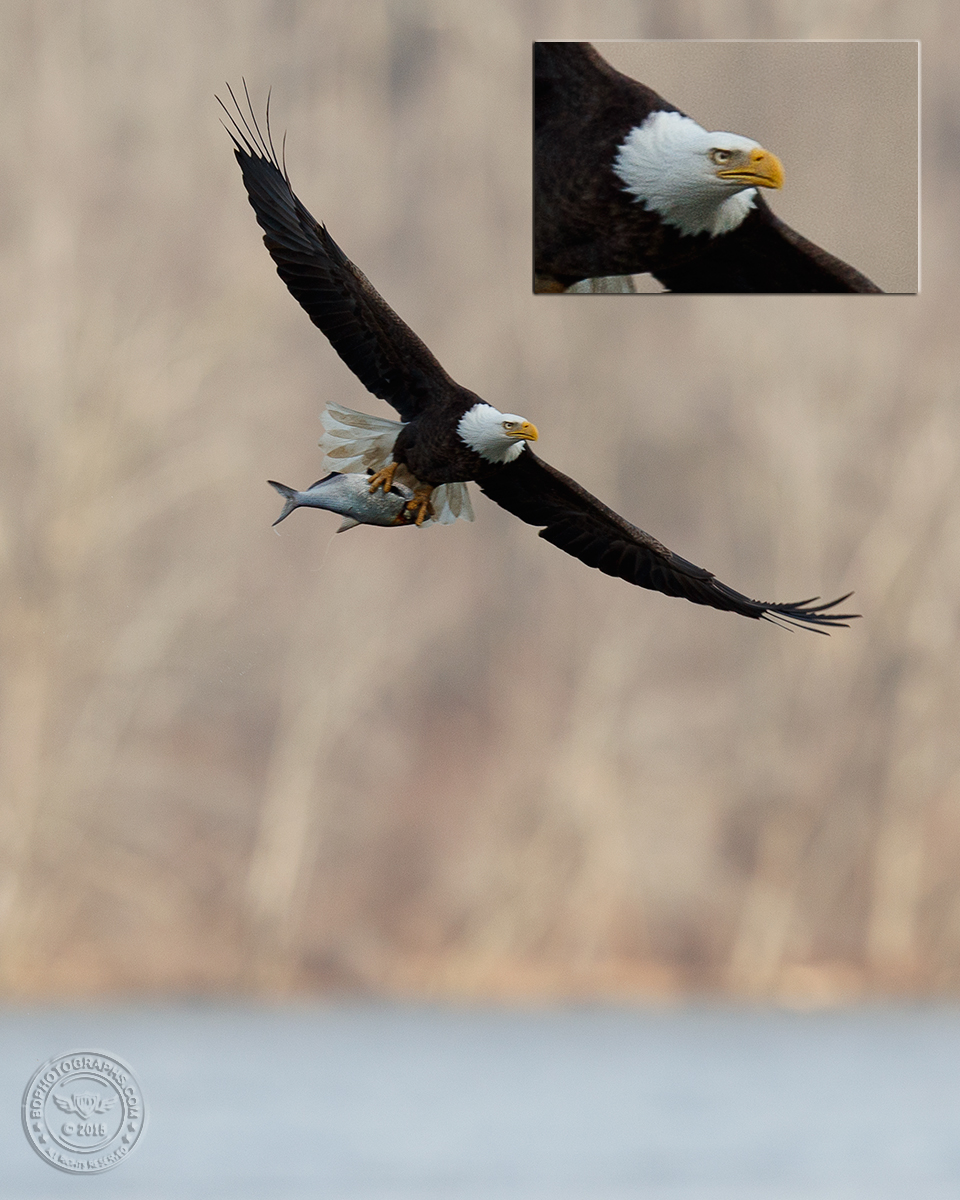

CHANGE YOUR SUBJECT

A dull sunset might force you to completely rethink your photoshoot. In general it helps to narrow your framing when light is not favorable. In this image, the soft light was pleasing, but the sky was drab and lacking color. Instead of my original subject (a nearby marina at sunset), I chose this snow-covered vintage Mercedes. The winter sunset is implied by the reflections without featuring directly in the scene.

Sometimes a sunset is better captured with subtlety