A typical canyon view in Utah. It is easily a top contender for the state with the most natural beauty.

I’ve visited most of the 50 states and while I’d like to see them all, that goal is constantly pushed out as I return to my favorites over and over again. The deserts and mountains of the American west are my top places to visit in the US, most recently to eastern Utah and the alien landscapes of the Colorado Plateau. The buttes, badlands, arches, and canyons form some of the most famous and iconic structures in the country: one, Delicate Arch, is instantly recognizable from its appearance on the Utah license plate.

I concentrated on eastern Utah in part because of its remoteness (the nearest airport served by major airlines is in Grand Junction, Colorado) and because of the many interesting formations in the backcountry areas. Three of Utah’s big five national parks are in the region (Capitol Reef, Canyonlands, and Arches) and they are less crowded than the two in the western part of the state (Bryce Canyon, Zion) both of which are within a few hours’ drive from Las Vegas. Dead Horse Point State Park and Goblin Valley State Park both feature fantastic photo opportunities and the locations in BLM (Bureau of Land Management) areas are spectacular.

The only photo I have of myself on this trip. A solid 4x4 is a must for off-road locations.

Although this was primarily a landscape photography trip, I also planned several drone shots and, with the help of clear weather, a couple of attempts to photograph the Milky Way in the night sky. I timed the trip to occur in the days after a new moon and before the arrival of the summer heat. Although I visited nearly six weeks before summer solstice, the days were already long: sunrise shortly after 6 a.m. and twilight at nearly 9 p.m. The Milky Way galactic core appeared just before midnight, leaving only a few hours to sleep at night. When I first began my journey in photography, I would wake up for sunrise regardless of the forecast, but over the years I’ve become more discriminating and less inclined to force an early rise if conditions aren’t favorable for the shot I’m trying to achieve. In any case, the itineraries for this trip were jam-packed to take advantage of the best light each day,

To get around safely, I secured a high-clearance Jeep 4x4 designed for backcountry exploring. Most days I drove to at least one off-road location, often miles away from a paved highway. Some roads were simple dusty trails; others were rocky, snaking paths with deep washboarding and sandy dugouts. Significant pre-planning and many hours of research were critical to identifying the routes and plotting the locations. Alright, enough preamble: let’s get to the images!

The portfolio shot from this adventure

My favorite image of the trip turned out to be this sunset drone photo of a sandstone butte. It is illegal to fly in the national parks so I knew that opportunities would limited to locations outside those areas. Thankfully Utah has many amazing features in more drone-friendly places.

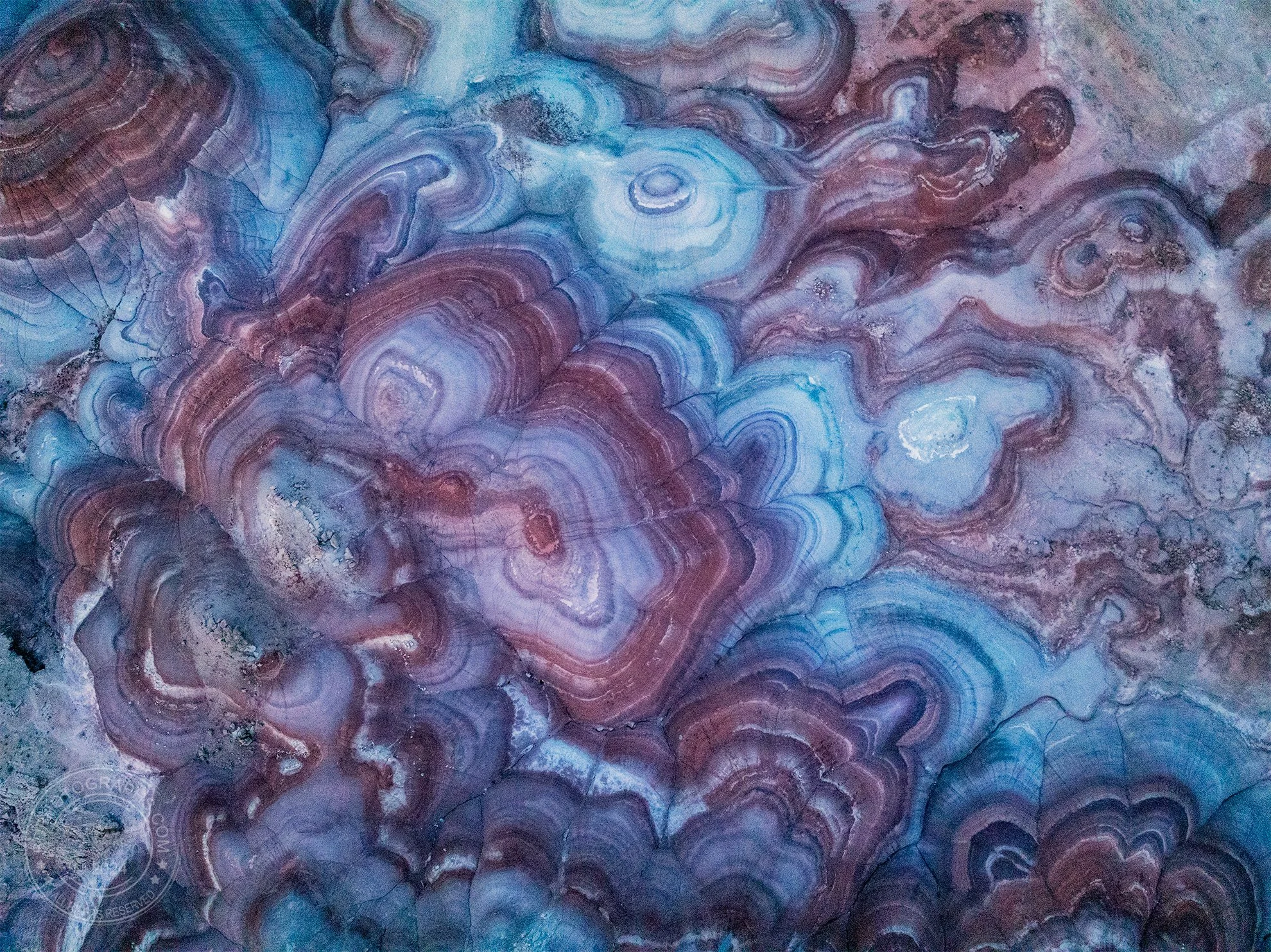

Top-down drone shots can produce interesting abstracts

Another drone shot I captured was outside of Hanksville at the “Rainbow Hills.” This one required minor off-roading and precise navigation — drone locations aren’t always obvious at ground level. Timing was key to achieving this image: blue hour after sunset cast a turquoise hue onto the sandstone hills. With the sun below the horizon, the light glowed with a soft, cool tone.

Temple of the Moon (center) bathed in golden light

One of the more adventurous itineraries was an afternoon trip in the Cathedral Valley section of Capitol Reef National Park. More than 17 miles of winding rough road led to the iconic Temple of the Sun and Temple of the Moon. I shuttled between the two pinnacles looking for compositions and taking advantage of the best light. After some time at Temple of the Sun, I hiked behind Temple of the Moon to photograph it in between two other giant slabs during golden hour. The secret to a shot like this is using elevation to align the three formations to similar heights in frame. I prefer to walk around to different vantage points to compose an image — and that means in three dimensions whenever possible. Eye level is the most conventional but frequently not the best perspective from which to shoot.

As the sun dipped toward the horizon, I hurried back to Temple of the Sun hoping for a dramatic sky. Clouds had formed throughout the afternoon so I thought there was a possibility to capture strong color at sunset. And what a show it turned out to be!

Temple of the Sun and (in the back left) Temple of the Moon. The monoliths are similar in size.

For all images on this trip I used my Canon R5 mirrorless camera. Recently I traded in my Canon EF 16-35mm F/4L IS lens — which was my primary landscape and underwater lens for many years. That lens served me beautifully, and many images in my portfolio were shot with it, but it was time to make a change for two reasons: 1) I wanted a single lens for landscape, underwater, and astrophotography and 2) I wanted a lens native to my mirrorless camera without having to use an adapter. So in Utah I debuted the Canon RF 15-35mm F/2.8L as my wide-angle choice.

When I first took an interest in landscape photography, I was constantly chasing colorful sunsets, and while I still do appreciate a brilliant sky, I find that my favorite images often are golden hour landscapes in which the subject is bathed in magical light. Likewise, blue hour is my preferred condition for cityscapes, even more so than spectacular sunsets. Of course in the desert boring blue skies are common, especially in the cooler months, but during my week in Utah I experienced a mix of sun and cloudy skies — so often in fact, that on a few nights clouds obscured the night sky and prevented me from photographing the Milky Way. Eventually the weather cleared and I was able to take advantage of Utah’s famously dark skies.

One of the most peculiar locations I shot is called the Moonscape Overlook: a bluff carved out over magnificent badlands. Early morning sunrise unquestionably is the best time to photograph this spot and only while the sun just peeks over the horizon. I set my alarm for a 4:30 a.m. wakeup and arrived in time to scout compositions and find my preferred angle. A few other photographers and campers were there too, and one adventurous woman volunteered to step out onto the pinnacle overlooking the canyon. I have to confess some anxiety as I watched her step out onto the landing, knowing that I’d be powerless to help in the event of a tragedy. But she was surefooted and confident and turned out to be an excellent model for the few photographers capturing the sunrise. Normally I try to avoid including people in my shot, but in some instances a well-placed model can help to provide scale, especially in vast panoramic settings.

A beautiful sunrise in the Moonscape. The woman standing on the pinnacle said she had no fear of the 1400 foot drop to the canyon below.

After a few days it was time to travel east toward Moab where I would focus on subjects in Arches and Canyonlands National Parks. I originally wrote off Mesa Arch in Canyonlands. It is one of the most photographed locations in the southwest, drawing an assembly of photographers in the middle of the night to camp out and claim one of the few prime spots for sunrise.

Mesa Arch, despite its name, is in Canyonlands National Park, not Arches National Park.

I did not have any interest in repeating that shot, so I went in the late afternoon just to see the location. I expected crowds and no photo opportunity, but to my astonishment, there was no one at the arch when I arrived! So I quickly took a few photos and enjoyed the quiet view. A few minutes later, a number of people showed up and the arch was once again crowded.

My final stop was in Arches National Park to photograph the iconic Delicate Arch. I began the long uphill hike in the late afternoon, with dinner and beverages packed along with my camera gear. As the sun dropped toward the horizon the light took on a rich amber tone, painting the sandstone in gold. In settings like this, when the light is right, a great photo is a slam dunk — you simply need to put yourself there at the right time. The light faded and I enjoyed a sunset dinner. It was time to begin the downhill climb and rest a few hours. At midnight I would attempt another Milky Way photo and the next morning I had to catch a flight out of Grand Junction, two hours away.

Delicate Arch — icon of the Utah license plate — is arguably the most famous arch in the United States.